“Harmony and Form” in Western Classical Music are fundamental pillars that have guided the evolution of the art form for centuries. Harmony refers to the simultaneous combination of notes, especially when arranged in chords and progressions that are pleasing to the ear. It acts as the vertical dimension of music, creating depth and emotional resonance. Contrarily, form is the structural blueprint of a musical composition, representing the manner in which musical ideas are organized and repeated, giving a piece its unique shape and progression.

These elements combine to provide music with an architectural coherence, ensuring that even the most complex pieces are accessible to the listener’s ear. Throughout the various eras of classical music, from the intricate polyphony of the Baroque to the expressive Romantic and the innovative Modern periods, harmony and form have been continuously explored, expanded, and redefined, fueling the timeless beauty and innovation of Western Classical Music.

Table of Contents

Harmony and Form

5.1 Triads

Harmony in Western music (Section 2.8) is based on triads. Triads are simple three-note chords (Chords) built of thirds.

5.1.1 Triads in Root Position

The chords in Figure 5.1 (Triads in Root Position) are written in root position, which is the most basic way to write a triad. In root position, the root, which is the note that names the chord, is the lowest note. The third of the chord is written a third (Figure 4.26: Simple Intervals) higher than the root, and the fth of the chord is written a fth (Figure 4.26: Simple Intervals) higher than the root (which is also a third higher than the third of the chord). So the simplest way to write a triad is as a stack of thirds, in root position.

note: The type of interval or chord – major, minor, diminished, etc., is not important when you are determining the position of the chord. To simplify things, all notes in the examples and exercises below

are natural, but it would not change their position at all if some notes were sharp or at. It would, however, change the name of the triad – see Naming Triads.

Exercise 5.1.1

Write a triad in root position using each root given. If you need some sta paper for exercises you can print this PDF le

5.1.2 First and Second Inversions

Any other chord that has the same-named notes as a root position chord is considered to be essentially the same chord in a di erent position. In other words, all chords that have only D naturals, F sharps, and A naturals, are considered D major chords.

note: But if you change the pitch or spelling of any note in the triad, you have changed the chord (see Naming Triads). For example, if the F sharps are written as G ats, or if the A’s are sharp instead of natural, you have a di erent chord, not an inversion of the same chord. If you add notes, you have also changed the name of the chord (see Beyond Triads). You cannot call one chord the inversion of another if either one of them has a note that does not share a name (for example “F sharp” or “B natural”) with a note in the other chord.

If the third of the chord is the lowest note, the chord is in rst inversion. If the fth of the chord is the lowest note, the chord is in second inversion. A chord in second inversion may also be called a six-four chord, because the intervals in it are a sixth and a fourth.

It does not matter how far the higher notes are from the lowest note, or how many of each note there are

(at di erent octaves or on di erent instruments); all that matters is which note is lowest. (In fact, one of the notes may not even be written, only implied by the context of the chord in a piece of music. A practiced ear will tell you what the missing note is; we won’t worry about that here.) To decide what position a chord is in, move the notes to make a stack of thirds and identify the root.

Example 5.1

Example 5.2

Exercise 5.1.2

Rewrite each chord in root position, and name the original position of the chord.

5.2 Naming Triads

The position that a chord is in does make a di erence in how it sounds, but it is a fairly small di erence. Listen4 to a G major chord in three di erent positions.

A much bigger di erence in the chord’s sound comes from the intervals between the rootposition notes of the chord. For example, if the B in one of the chords above was changed to a B at, you would still have a G triad, but the chord would now sound very di erent. So chords are named according to the intervals between the notes when the chord is in root position. Listen5 to four di erent G chords.

5.2.1 Major and Minor Chords

The most commonly used triads form major chords and minor chords. All major chords and minor chords have an interval of a perfect fth between the root and the fth of the chord. A perfect fth (7 half-steps) can be divided into a major third (Major and Minor Intervals,) (4 half-steps) plus a minor third (Major and Minor Intervals, ) (3 half-steps). If the interval between the root and the third of the chord is the major third (with the minor third between the third and the fth of the chord), the triad is a major chord. If the interval between the root and the third of the chord is the minor third (and the major third is between the third and fth of the chord), then the triad is a minor chord. Listen closely to a major triad and a minor triad .

Example 5.3

Example 5.4

Exercise 5.2.1

Write the major chord for each root given.

Exercise 5.2.2

Write the minor chord for each root given.

5.2.2 Augmented and Diminished Chords

Because they don’t contain a perfect fth, augmented and diminished chords have an unsettled feeling and are normally used sparingly. An augmented chord is built from two major thirds, which adds up to an augmented fth. A diminished chord is built from two minor thirds, which add up to a diminished fth. Listen closely to an augmented triad and a diminished triad .

Example 5.5

Exercise 5.2.3

Write the augmented triad for each root given.

Exercise 5.2.4

Write the diminished triad for each root given.

Notice that you can’t avoid double sharps or double ats by writing the note on a di erent space or line. If you change the spelling of a chord’s notes, you have also changed the chord’s name. For example, if, in an augmented G sharp major chord, you rewrite the D double sharp as an E natural, the triad becomes an E augmented chord

You can put the chord in a di erent position (Section 5.1) or add more of the same-named notes at other octaves without changing the name of the chord. But changing the note names or adding di erent-named notes, will change the name of the chord. Here is a summary of the intervals in triads in root position.

Figure 5.17

Exercise 5.2.5

Now see if you can identify these chords that are not necessarily in root position. Rewrite them in root position rst if that helps

5.3 Consonance and Dissonance

Notes that sound good together when played at the same time are called consonant. Chords built only of consonances sound pleasant and “stable”; you can listen to one for a long time without feeling that the music needs to change to a di erent chord. Notes that are dissonant can sound harsh or unpleasant when played at the same time.

Or they may simply feel “unstable”; if you hear a chord with a dissonance in it, you may feel that the music is pulling you towards the chord that resolves the dissonance. Obviously, what seems pleasant or unpleasant is partly a matter of opinion. This discussion only covers consonance and dissonance in Western music.

note: For activities that introduce these concepts to young students, please see Consonance and Dissonance Activities .

Of course, if there are problems with tuning, the notes will not sound good together, but this is not what consonance and dissonance are about. (Please note, though, that the choice of tuning system can greatly a ect which intervals sound consonant and which sound dissonant! Please see Tuning Systems for more about this.)

Consonance and dissonance refer to intervals and chords (Chords, ). The interval between two notes is the number of half steps between them, and all intervals have a name that musicians commonly use, like major third (Major and Minor Intervals,) (which is 4 half steps), perfect fth (7 half steps), or octave. (See Interval to learn how to determine and name the interval between any two notes.)

An interval is measured between two notes. When there are more than two notes sounding at the same time, that’s a chord. (See Triads , Naming Triads, and Beyond Triads (Section 5.4) for some basics on chords.) Of course, you can still talk about the interval between any two of the notes in a chord.

The simple intervals that are considered to be consonant are the minor third12, major third13, perfect fourth14, perfect fth15, minor sixth16, major sixth17, and the octave18.

In modern Western Music, all of these intervals are considered to be pleasing to the ear. Chords that contain only these intervals are considered to be “stable”, restful chords that don’t need to be resolved. When we hear them, we don’t feel a need for them to go to other chords.

The intervals that are considered to be dissonant are the minor second19, the major second20, the minor seventh21, the major seventh22, and particularly the tritone23, which is the interval in between the perfect fourth and perfect fth.

These intervals are all considered to be somewhat unpleasant or tension-producing. In tonal music (p. 87), chords containing dissonances are considered “unstable”; when we hear them, we expect them to move on to a more stable chord. Moving from a dissonance to the consonance that is expected to follow it is called resolution, or resolving the dissonance. The pattern of tension and release created by resolved dissonances is part of what makes a piece of music exciting and interesting. Music that contains no dissonances can tend to seem simplistic or boring.

On the other hand, music that contains a lot of dissonances that are never resolved (for example, much of twentieth-century “classical” or “art” music) can be di cult for some people to listen to, because of the unreleased tension.

Figure 5.21: In most music a dissonance will resolve; it will be followed by a consonant chord that it naturally leads to, for example a G seventh chord resolves to a C major chord , and a D suspended fourth resolves to a D major chord . A series of unresolved dissonances , on the other hand, can produce a sense of unresolved tension.

Why are some note combinations consonant and some dissonant? Preferences for certain sounds is partly cultural; that’s one of the reasons why the traditional musics of various cultures can sound so di erent from each other. Even within the tradition of Western music, opinions about what is unpleasantly dissonant have changed a great deal over the centuries. But consonance and dissonance do also have a strong physical basis in nature.

In simplest terms, the sound waves of consonant notes ” t” together much better than the sound waves of dissonant notes. For example, if two notes are an octave apart, there will be exactly two waves of one note for every one wave of the other note. If there are two and a tenth waves or eleven twelfths of a wave of one note for every wave of another note, they don’t t together as well. For much more about the physical basis of consonance and dissonance, see Acoustics for Music Theory, Harmonic Series , and Tuning Systems.

5.4 Beyond Triads: Naming Other Chords

5.4.1 Introduction

Once you know how to name triads (please see Triads and Naming Triads), you need only a few more rules to be able to name all of the most common chords.

This skill is necessary for those studying music theory. It’s also very useful at a “practical” level for composers, arrangers, and performers (especially people playing chords, like pianists and guitarists), who need to be able to talk to each other about the chords that they are reading, writing, and playing.

Chord manuals, ngering charts, chord diagrams, and notes written out on a sta are all very useful, especially if the composer wants a very particular sound on a chord. But all you really need to know are the name of the chord, your major scales and minor scales, and a few rules, and you can gure out the notes in any chord for yourself.

What do you need to know to be able to name most chords?

1. You must know your major, minor, augmented and diminished triads. Either have them all memorized,or be able to gure them out following the rules for triads. (See Triads (Section 5.1) and Naming Triads .)

2. You must be able to nd intervals from the root of the chord. One way to do this is by using the rules for intervals. (See Interval.) Or if you know your scales and don’t want to learn about intervals, you can use the method in #3 instead.

3. If you know all your scales (always a good thing to know, for so many reasons), you can nd all the intervals from the root using scales. For example, the “4” in Csus4 is the 4th note in a C (major or minor) scale, and the “minor 7th” in Dm7 is the 7th note in a D (natural) minor scale. If you would prefer this method, but need to brush up on your scales, please see Major Keys and Scales and Minor Keys and Scales.

4. You need to know the rules for the common seventh chords (Section 5.4.3: Seventh Chords), forextending (Section 5.4.4: Added Notes, Suspensions, and Extensions) and altering (Section 5.4.6: Altering Notes and Chords) chords, for adding notes (Section 5.4.4: Added Notes, Suspensions, and Extensions), and for naming bass notes (Section 5.4.5: Bass Notes). The basic rules for these are all found below.

note: Please note that the modern system of chord symbols, discussed below, is very di erent from the gured bass shorthand popular in the seventeenth century (which is not discussed here). For example, the “6” in gured bass notation implies the rst inversion chord, not an added 6. (As of this writing, there was a very straightforward summary of gured bass at Ars Nova Software .)

5.4.2 Chord Symbols

Some instrumentalists, such as guitarists and pianists, are sometimes expected to be able to play a named chord, or an accompaniment (Accompaniment, ) based on that chord, without seeing the notes written out in common notation. In such cases, a chord symbol above the sta tells the performer what chord should be used as accompaniment to the music until the next symbol appears.

Figure 5.22: A chord symbol above the sta is sometimes the only indication of which notes should be used in the accompaniment (Accompaniment,). Chord symbols also may be used even when an accompaniment is written out, so that performers can read either the chord symbol or the notated music, as they prefer.

There is widespread agreement on how to name chords, but there are several di erent systems for writing chord symbols. Unfortunately, this can be a little confusing, particularly when di erent systems use the same symbol to refer to di erent chords. If you’re not certain what chord is wanted, you can get useful clues both from the notes in the music and from the other chord symbols used. (For example, if the “minus” chord symbol is used, check to see if you can spot any chords that are clearly labelled as either minor or diminished.)

Figure 5.23: There is unfortunately a wide variation in the use of chord symbols. In particular, notice that some symbols, such as the “minus” sign and the triangle, can refer to di erent chords, depending on the assumptions of the person who wrote the symbol

5.4.3 Seventh Chords

If you take a basic triad (Section 5.1) and add a note that is a seventh above the root, you have a seventh chord. There are several di erent types of seventh chords, distinguished by both the type of triad and the type of seventh used. Here are the most common.

Seventh Chords

• Seventh (or “dominant seventh”) chord = major triad + minor seventh

• Major Seventh chord = major triad + major seventh

• Minor Seventh chord = minor triad + minor seventh

• Diminished Seventh chord = diminished triad + diminished seventh (half step lower than a minor seventh)

• Half-diminished Seventh chord = diminished triad + minor seventh

An easy way to remember where each seventh is:

• The major seventh is one half step below the octave.

• The minor seventh is one half step below the major seventh.

• The diminished seventh is one half step below the minor seventh.

Listen to the di erences between the C seventh30, C major seventh31, C minor seventh32, C diminished seventh33, and C half-diminished seventh34.

Exercise 5.4.1

Write the following seventh chords. If you need sta paper, you can print this PDF le35

1. G minor seventh

2. E (dominant) seventh

3. B at major seventh

4. D diminished seventh

5. F (dominant) seventh

6. F sharp minor seventh

5.4.4 Added Notes, Suspensions, and Extensions

The seventh is not the only note you can add to a basic triad to get a new chord. You can continue to extend the chord by adding to the stack of thirds, or you can add any note you want. The most common additions and extensions add notes that are in the scale named by the chord.

The rst, third, and fth (1, 3, and 5) notes of the scale are part of the basic triad. So are any other notes in other octaves that have the same name as 1, 3, or 5. In a C major chord, for example, that would be any C naturals, E naturals, and G naturals. If you want to add a note with a di erent name, just list its number (its scale degree) after the name of the chord.

Figure 5.26: Labelling a number as “sus” (suspended) implies that it replaces the chord tone immediately below it. Labelling it “add” implies that only that note is added. In many other situations, the performer is left to decide how to play the chord most e ectively. Chord tones may or may not be left out. In an extended chord, all or some of the notes in the “stack of thirds” below the named note may also be added.

Many of the higher added notes are considered extensions of the “stack of thirds” begun in the triad. In other words, a C13 can include (it’s sometimes the performer’s decision which notes will actually be played) the seventh, ninth, and eleventh as well as the thirteenth. Such a chord can be dominant, major, or minor; the performer must take care to play the correct third and seventh. If a chord symbol says to “add13”, on the other hand, this usually means that only the thirteenth is added.

note: All added notes and extensions, including sevenths, introduce dissonance into the chord. In some modern music, many of these dissonances are heard as pleasant or interesting or jazzy and don’t need to be resolved. However, in other styles of music, dissonances need to be resolved, and some chords may be altered to make the dissonance sound less harsh (for example, by leaving out the 3 in a chord with a 4).

You may have noticed that, once you pass the octave (8), you are repeating the scale. In other words, C2 and C9 both add a D, and C4 and C11 both add an F. It may seem that C4 and C11 should therefore be the same chords, but in practice these chords usually do sound di erent; for example, performers given a C4 chord will put the added note near the bass note and often use it as a temporary replacement for the third (the “3”) of the chord.

On the other hand, they will put the added note of a C11 at the top of the chord, far away from the bass note and piled up on top of all the other notes of the chord (including the third), which may include the 7 and 9 as well as the 11. The result is that the C11 – an extension – has a more di use, jazzy, or impressionistic sound. The C4, on the other hand, has a more intense, needs-to-be-resolved, classic suspension sound. In fact, 2, 4, and 9 chords are often labelled suspended (sus), and follow the same rules for resolution (p. 176) in popular music as they do in classical.

5.4.5 Bass Notes

The bass line (Accompaniment, p. 81) of a piece of music is very important, and the composer/arranger often will want to specify what note should be the lowest-sounding in the chord. At the end of the chord name will be a slash followed by a note name, for example C/E. The note following the slash should be the bass note.

The note named as the bass note can be a note normally found in the chord – for example, C/E or C/G – or it can be an added note – for example C/B or C/A. If the bass note is not named, it is best to use the tonic (p. 121) as the primary bass note.

Exercise 5.4.3

Name the chords. (Hint: Look for suspensions, added notes, extensions, and basses that are not the root. Try to identify the main triad or root rst.)

Exercise 5.4.4

For guitarists, pianists, and other chord players: Get some practical practice. Name some chords you don’t have memorized (maybe F6, Am/G, Fsus4, BM7, etc.). Chords with ngerings that you don’t know but with a sound that you would recognize work best for this exercise. Decide what notes must be in those chords, nd a practical ngering for them, play the notes and see what they sound like.

5.4.6 Altering Notes and Chords

If a note in the chord is not in the major or minor scale of the root of the chord, it is an altered note and makes the chord an altered chord. The alteration – for example ” at ve” or “sharp nine” – is listed in the chord symbol. Any number of alterations can be listed, making some chord symbols quite long. Alterations are not the same as accidentals. Remember, a chord symbol always names notes in the scale of the chord root , ignoring the key signature of the piece that the chord is in, so the alterations are from the scale of the chord, not from the key of the piece.

Figure 5.31: There is some variation in the chord symbols for altered chords. Plus/minus or sharp/ at symbols may appear before or after the note number. When sharps and ats are used, remember that the alteration is always from the scale of the chord root, not from the key signature.

Exercise 5.4.5

On a treble clef sta , write the chords named. You can print this PDF le if you need sta paper for this exercise.

1. D (dominant) seventh with a at nine

2. A minor seventh with a at ve

3. G minor with a sharp seven

4. B at (dominant) seventh with a sharp nine

5. F nine sharp eleven

5.5 Beginning Harmonic Analysis

5.5.1 Introduction

It sounds like a very technical idea, but basic harmonic analysis just means understanding how a chord is related to the key and to the other chords in a piece of music. This can be such useful information that you will nd many musicians who have not studied much music theory, and even some who don’t read music, but who can tell you what the I (“one”) or the V (” ve”) chord are in a certain key. Why is it useful to know how chords are related?

• Many standard forms (for example, a “twelve bar blues”) follow very speci c chord progressions (Chords, p. 80), which are often discussed in terms of harmonic relationships.

• If you understand chord relationships, you can transpose any chord progression you know to any key (Section 4.3) you like.

• If you are searching for chords to go with a particular melody (in a particular key), it is very helpful to know what chords are most likely in that key, and how they might be likely to progress from one to another.

• Improvisation requires an understanding of the chord progression.

• Harmonic analysis is also necessary for anyone who wants to be able to compose reasonable chord progressions or to study and understand the music of the great composers.

5.5.2 Basic Triads in Major Keys

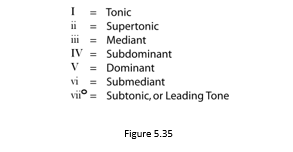

Any chord might show up in any key, but some chords are much more likely than others. The most likely chords to show up in a key are the chords that use only the notes in that key (no accidentals). So these chords have both names and numbers that tell how they t into the key. (We’ll just discuss basic triads for the moment, not seventh chords or other added-note (Section 5.4.4: Added Notes, Suspensions, and Extensions) or altered chords.) The chords are numbered using Roman numerals from I to vii.

Exercise 5.5.1

Write and name the chords in G major and in B at major. (Hint: Determine the key signature rst. Make certain that each chord begins on a note in the major scale and contains only notes in the key signature.) If you need some sta paper, you can print this PDF le

You can nd all the basic triads that are possible in a key by building one triad, in the key, on each note of the scale (each scale degree). One easy way to name all these chords is just to number them: the chord that starts on the rst note of the scale is “I”, the chord that starts on the next scale degree is “ii”, and so on. Roman numerals are used to number the chords. Capital Roman numerals are used for major chords (Section 5.2.1: Major and Minor Chords) and small Roman numerals for minor chords (Section 5.2.1: Major and Minor Chords). The diminished chord (Section 5.2.2: Augmented and Diminished Chords) is in small Roman numerals followed by a small circle.

Because major scales always follow the same pattern, the pattern of major and minor chords is also the same in any major key. The chords built on the rst, fourth, and fth degrees of the scale are always major chords (I, IV, and V). The chords built on the second, third, and sixth degrees of the scale are always minor chords (ii, iii, and vi). The chord built on the seventh degree of the scale is a diminished chord.

note: Notice that IV in the key of B at is an E at major chord, not an E major chord, and vii in the key of G is F sharp diminished, not F diminished. If you can’t name the scale notes in a key, you may nd it di cult to predict whether a chord should be based on a sharp, at, or natural note. This is only one reason (out of many) why it is a good idea to memorize all the scales. (See Major Keys and Scales (Section 4.3).) However, if you don’t plan on memorizing all the scales at this time, you’ll nd it useful to memorize at least the most important chords (start with I, IV, and V) in your favorite keys.

5.5.3 A Hierarchy of Chords

Even among the chords that naturally occur in a key signature, some are much more likely to be used than others. In most music, the most common chord is I. In Western music (Section 2.8), I is the tonal center (Section 4.3) of the music, the chord that feels like the “home base” of the music.

As the other two major chords in the key, IV and V are also likely to be very common. In fact, the most common added-note chord in most types of Western music is a V chord (the dominant chord (Section 5.5.4: Naming Chords Within a Key)) with a minor seventh (Major and Minor Intervals) added (V7). It is so common that this particular avor of seventh (Section 5.4.3: Seventh Chords) (a major chord with a minor seventh added) is often called a dominant seventh, regardless of whether the chord is being used as the V (the dominant) of the key.

Whereas the I chord feels most strongly “at home”, V7 gives the strongest feeling of “time to head home now”. This is very useful for giving music a satisfying ending. Although it is much less common than the V7, the diminished vii chord (often with a diminished seventh (Section 5.2.2: Augmented and Diminished Chords) added), is considered to be a harmonically unstable chord that strongly wants to resolve to I.

Listen to these very short progressions and see how strongly each suggests that you must be in the key of C: C (major) chord(I)41; F chord to C chord (IV – I)42; G chord to C chord (V – I)43; G seventh chord to C chord (V7 – I)44; B diminished seventh chord to C chord (viidim7 – I)45 (Please see Cadence (Section 5.6) for more on this subject.)

Many folk songs and other simple tunes can be accompanied using only the I, IV and V (or V7) chords of a key, a fact greatly appreciated by many beginning guitar players. Look at some chord progressions from real music.

Typically, folk, blues, rock, marches, and Classical-era music is based on relatively straightforward chord progressions, but of course there are plenty of exceptions. Jazz and some pop styles tend to include many chords with added (Section 5.4.4: Added Notes, Suspensions, and Extensions) or altered notes. Romantic-era music also tends to use more complex chords in greater variety, and is very likely to use chords that are not in the key.

Extensive study and practice are needed to be able to identify and understand these more complex progressions. It is not uncommon to nd college-level music theory courses that are largely devoted to harmonic analysis and its relationship to musical forms. This course will go no further than to encourage you to develop a basic understanding of what harmonic analysis is about.

5.5.4 Naming Chords Within a Key

So far we have concentrated on identifying chord relationships by number, because this system is commonly used by musicians to talk about every kind of music from classical to jazz to blues. There is another set of names that is commonly used, particularly in classical music, to talk about harmonic relationships. Because numbers are used in music to identify everything from beats to intervals to harmonics to what ngering to use, this naming system is sometimes less confusing.

Exercise 5.5.2

Name the chord.

1. Dominant in C major

2. Subdominant in E major

3. Tonic in G sharp major

4. Mediant in F major

5. Supertonic in D major

6. Submediant in C major

7. Dominant seventh in A major (Solution on p. 205.)

Exercise 5.5.3

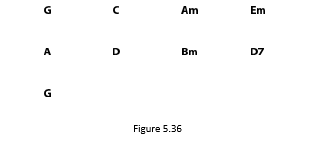

The following chord progression is in the key of G major. Identify the relationship of each chord to the key by both name and number. Which chord is not in the key? Which chord in the key has been left out of the progression?

5.5.5 Minor Keys

Since minor scales (Section 4.4) follow a di erent pattern of intervals (Section 4.5) than major scales, they will produce chord progressions with important di erences from major key chord progressions.

Exercise 5.5.4

Write (triad) chords that occur in the keys of A minor, E minor, and D minor. Remember to begin each triad on a note of the natural minor (Section 4.4.3: Relative Minor and Major Keys) scale and to include only notes in the scale in each chord. Which chord relationships are major? Which minor? Which diminished? If you need sta paper, print this PDF le

Notice that the actual chords created using the major scale and its relative minor (Section 4.4.3: Relative Minor and Major Keys) scale are the same. For example, compare the chords in A minor (Figure 5.54) to the chords in C major (Figure 5.32 (Chords in the keys of C major and D major)).

The di erence is in how the chords are used. As explained above, if the key is C major, the chord progression (Chords,) will likely make it clear that C is the tonal center (p. 121) of the piece, for example by featuring the bright-sounding (major) tonic, dominant, and subdominant chords (C major, G major or G7, and F major), particularly in strong cadences (Section 5.6) that end on a C chord.

If the piece is in A minor, on the other hand, it will be more likely to feature (particularly in cadences) the tonic, dominant, and subdominant of A minor (the A minor, D minor, and E minor chords). These chords are also available in the key of C major, of course, but they typically are not given such a prominent place.

As mentioned above (p. 187), the ” avor” of sound that is created by a major chord with a minor seventh added, gives a particularly dominant (wanting-to-go-to-the-home-chord) sound, which in turn gives a more strong feeling of tonality to a piece of music. Because of this, many minor pieces change the dominant chord so that it is a dominant seventh (a major chord with a minor seventh), even though that requires using a note that is not in the key.

Exercise 5.5.5

Look at the chords in Figure 5.54. What note of each scale would have to be changed in order to make v major? Which other chords would be a ected by this change? What would they become, and are these altered chords also likely to be used in the minor key?

The point of the harmonic minor (Section 4.4.3: Relative Minor and Major Keys) scale is to familiarize the musician with this common feature of harmony, so that the expected chords become easy to play in every minor key. There are also changes that can be made to the melodic lines of a minor-key piece that also make it more strongly tonal. This involves raising (by one half step) both the sixth and seventh scale notes, but only when the melody is ascending.

So the musician who wants to become familiar with melodic patterns in every minor key will practice melodic minor (Section 4.4.3: Relative Minor and Major Keys) scales, which use di erent notes for the ascending and descending scale.

You can begin practicing harmonic analysis by practicing identifying whether a piece is in the major key or in its relative minor. Pick any piece of music for which you have the written music, and use the following steps to determine whether the piece is major or minor:

Is it Major or Minor?

• Identify the chords used in the piece, particularly at the very end, and at other important cadences (Section 5.6) (places where the music comes to a stopping or resting point). This is an important rst step that may require practice before you become good at it. Try to start with simple music which either includes the names of the chords, or has simple chords in the accompaniment that will be relatively easy to nd and name. If the chords are not named for you and you need to review how to name them just by looking at the written notes, see Naming Triads (Section 5.2) and Beyond Triads.

• Find the key signature.

• Determine both the major key represented by that key signature, and its relative minor (Section 4.4.3: Relative Minor and Major Keys) (the minor key that has the same key signature).

• Look at the very end of the piece. Most pieces will end on the tonic chord. If the nal chord is the tonic of either the major or minor key for that key signature, you have almost certainly identi ed the key.

• If the nal chord is not the tonic of either the major or the minor key for that key signature, there are two possibilities. One is that the music is not in a major or minor key! Music from other cultures,

as well as some jazz, folk, modern, and pre-Baroque European music are based on other modes or scales. (Please see Modes and Ragas and Scales that aren’t Major or Minor for more about this.) If the music sounds at all “exotic” or “unusual”, you should suspect that this may be the case.

• If the nal chord is not the tonic of either the major or the minor key for that key signature, but you still suspect that it is in a major or minor key (for example, perhaps it has a “repeat and fade” ending which avoids coming to rest on the tonic), you may have to study the rest of the music in order to discern the key. Look for important cadences before the end of the music (to identify I). You may be able to identify, just by listening, when the piece sounds as if it is approaching and landing on its “resting place”.

Also look for chords that have that “dominant seventh” avor (to identify V). Look for the speci c accidentals that you would expect if the harmonic minor (Section 4.4.3: Relative Minor and Major Keys) or melodic minor (Section 4.4.3: Relative Minor and Major Keys) scales were being used. Check to see whether the major or minor chords are emphasized overall. Put together the various clues to reach your nal decision, and check it with your music teacher or a musician friend if possible.

5.5.6 Modulation

Sometimes a piece of music temporarily moves into a new key. This is called modulation. It is very common in traditional classical music; long symphony and concerto movements almost always spend at least some time in a di erent key (usually a closely related key (Section 4.7) such as the dominant (Section 5.5.4: Naming Chords Within a Key) or subdominant (Section 5.5.4: Naming Chords Within a Key), or the relative minor or relative major (Section 4.4.3: Relative Minor and Major Keys)), in order to keep things interesting.

Shorter works, even in classical style, are less likely to have complete modulations. Abrupt changes of key can seem unpleasant and jarring. In most styles of music, modulation is accomplished gradually, using a progression of chords that seems to move naturally towards the new key. But implied modulations, in which the tonal center seems to suddenly shift for a short time, can be very common in some shorter works (jazz standards, for example).

As in longer works, modulation, with its new set of chords, is a good way to keep a piece interesting. If you nd that the chord progression in a piece of music suddenly contains many chords that you would not expect in that key, it may be that the piece has modulated. Lots of accidentals, or even an actual change of key signature (Section 1.1.4), are other clues that the music has modulated.

A new key signature (Section 1.1.4) may help you to identify the modulation key.

If there is not a change of key signature, remember that the new key is likely to contain whatever accidentals (p. 15) are showing up. It is also likely that many of the chords in the progression will be chords that are common in the new key. Look particularly for tonic chords and dominant sevenths. The new key is likely to be closely related (Section 4.7) to the original key, but another favorite trick in popular music is to simply move the key up one whole step (Section 4.2), for example from C major to D major.

Modulations can make harmonic analysis much more challenging, so try to become comfortable analyzing easier pieces before tackling pieces with modulations.

5.5.7 Further Study

Although the concept of harmonic analysis is pretty basic, actually analyzing complex pieces can be a major challenge. This is one of the main elds of study for those who are interested in studying music theory at a more advanced level. One next step for those interested in the subject is to become familiar with all the ways notes may be added to basic triads.

(Please see Beyond Triads for an introduction to that subject.) At that point, you may want to spend some time practicing analyzing some simple, familiar pieces. Depending on your interests, you may also want to spend time creating pleasing chord progressions by choosing chords from the correct key that will complement a melody that you know. As of this writing, the site Music Theory for Songwriters featured “chord maps” that help the student predict likely chord progressions.

For more advanced practice, look for music theory books that focus entirely on harmony or that spend plenty of time analyzing harmonies in real music. (Some music history textbooks are in this category.) You will progress more quickly if you can nd books that focus on the music genre that you are most interested in (there are books speci cally about jazz harmony, for example).

5.6 Cadence (Understanding Basic Music Theory)

A cadence is any place in a piece of music that has the feel of an ending point. This can be either a strong, de nite stopping point – the end of the piece, for example, or the end of a movement or a verse – but it also refers to the “temporary-resting-place” pauses that round o the ends of musical ideas within each larger section.

A musical phrase (Section 2.3.4: Melodic Phrases), like a sentence, usually contains an understandable idea, and then pauses before the next idea starts. Some of these musical pauses are simply take-a-breath-type pauses, and don’t really give an “ending” feeling. In fact, like questions that need answers, many phrases leave the listener with a strong expectation of hearing the next, “answering”, phrase.

Other phrases, though, end with a more de nite “we’ve arrived where we were going” feeling. The composer’s expert control over such feelings of expectation and arrival are one of the main sources of the listener’s enjoyment of the music.

Like a story, a piece of music can come to an end by simply stopping, but most listeners will react to such abruptness with dissatisfaction: the story or music simply “stopped” instead of “ending” properly. A more satisfying ending, in both stories and music, is usually provided by giving clues that an end is coming, and then ending in a commonly-accepted way. Stories are also divided into paragraphs, chapters, stanzas, scenes, or episodes, each with their own endings, to help us keep track of things and understand what is going on.

Music also groups phrases and motifs (Section 2.3.5: Motif) into verses, choruses, sections, and movements, marked o by strong cadences to help us keep track of them. In good stories, there are clues in the plot and the pacing – in the Western tradition, the chase gets more exciting, characters good and bad get what they deserve, the inevitable tragedy occurs, or misunderstandings get resolved – that signal that the end of the story is nearing. Similarly, in music there are clues that signal to the listener that the end is coming up.

These clues may be in the form; in the development of the musical ideas; in the music’s tempo, texture, or rhythmic complexity; in the chord progression (Chords,); even in the number and length of the phrases (Section 2.3.4: Melodic Phrases) (Western listeners are fond of powers of two ). Like the ending of a story, an ending in music is more satisfying if it follows certain customs that the listener expects to hear.

If you have grown up listening to a particular musical tradition, you will automatically have these expectations for a piece of music, even if you are not aware of having them. And like the customs for storytelling, these expectations can be di erent in di erent musical traditions.

Some things that produce a feeling of cadence

• Harmony – In most Western and Western-in uenced music (including jazz and “world” musics), harmony is by far the most important signal of cadence. One of the most fundamental “rules” of the major-minor harmony system is that music ends on the tonic. A tonal piece of music will almost certainly end on the tonic chord, although individual phrases or sections may end on a di erent chord (the dominant is a popular choice).

But a composer cannot just throw in a tonic chord and expect it to sound like an ending; the harmony must “lead up to” the ending and make it feel inevitable (just as a good story makes the ending feel inevitable, even if it’s a surprise). So the term cadence, in tonal music, usually refers to the “ending” chord plus the short chord progression (Chords) that led up to it.

There are many di erent terms in use for the most common tonal cadences; you will nd the most common terms below (Some Tonal Cadence Terms). Some (but not all) modal musics also use harmony to indicate cadence, but the cadences used can be quite di erent from those in tonal harmony.

• Melody – In the major/minor tradition, the melody will normally end on some note of the tonic chord triad, and a melody ending on the tonic will give a stronger (more nal-sounding) cadence than one ending on the third or fth of the chord. In some modal musics, the melody plays the most important role in the cadence. Like a scale, each mode also has a home note, where the melody is expected to end. A mode often also has a formula that the melody usually uses to arrive at the ending note.

For example, it may be typical of one mode to go to the nal note from the note one whole tone (p. 118) below it; whereas in another mode the penultimate note may be a minor third (p. 130) above the nal note. (Or a mode may have more than one possible melodic cadence, or its typical cadence may be more complex.)

• Rhythm – Changes in the rhythm (Section 2.1), a break or pause in the rhythm, a change in the tempo, or a slowing of or pause in the harmonic rhythm (Chords) are also commonly found at a cadence.

• Texture – Changes in the texture of the music also often accompany a cadence. For example, the music may momentarily switch from harmony to unison or from counterpoint to a simpler block-chord homophony (Section 2.4.2.2: Homophonic).

• Form – Since cadences mark o phrases and sections, form and cadence are very closely connected, and the overall architecture of a piece of music will often indicate where the next cadence is going to be – every eight measures for a certain type of dance, for example. (When you listen to a piece of music, you actually expect and listen for these regularly-spaced cadences, at least subconsciously. An accomplished composer may “tease” you by seeming to lead to a cadence in the expected place, but then doing something unexpected instead.)

Harmonic analysis, form, and cadence in Western music are closely interwoven into a complex subject that can take up an entire course at the college-music-major level. Complicating matters is the fact that there are several competing systems for naming cadences. This introductory course cannot go very deeply into this subject, and so will only touch on the common terms used when referring to cadences.

Unfortunately, the various naming systems may use the same terms to mean di erent things, so even a list of basic terms is a bit confusing.

Some Tonal Cadence Terms

• Authentic – A dominant (Section 5.5.4: Naming Chords Within a Key) chord followed by a tonic (p.

121) chord (V-I, or often V7-I).

• Complete Cadence – same as authentic cadence.

• Deceptive Cadence – This refers to times that the music seems to lead up to a cadence, but then doesn’t actually land on the expected tonic, and also often does not bring the expected pause in the music. A deceptive cadence is typically in a major key, and is the dominant followed by the submediant (Section 5.5.4: Naming Chords Within a Key) (V-vi). This means the substituted chord is the relative minor of the tonic chord.

• False Cadence – Same as deceptive cadence.

• Full Close – Same as authentic cadence.

• Half-cadence – May refer to a cadence that ends on the dominant chord (V). This type of cadence is more common at pause-type cadences than at full-stop ones. OR may have same meaning as plagal cadence.

• Half close – Same as plagal cadence.

• Imperfect Cadence – May refer to an authentic (V-I) cadence in which the chord is not in root position, or the melody does not end on the tonic. OR may mean a cadence that ends on the dominant chord (same as one meaning of half-cadence).

• Interrupted Cadence – Same as deceptive cadence.

• Perfect Cadence – Same as authentic cadence. As its name suggests, this is considered the strongest, most nal-sounding cadence. Some do not consider a cadence to be completely perfect unless the melody ends on the tonic and both chords (V and I) are in root position.

• Plagal Cadence – A subdominant (Section 5.5.4: Naming Chords Within a Key) chord followed by a tonic chord (IV-I). For many people, this cadence will be familiar as the “Amen” chords at the end of many traditional hymns.

• Semi-cadence – Same possible meanings as half cadence.

You can listen to a few simple cadences here: Perfect Cadence , Plagal Cadence , Half-cadence , Deceptive Cadence . The gure below also shows some very simple forms of some common cadences. The rst step in becoming comfortable with cadences is to start identifying them in music that is very familiar to you. Find the pauses and stops in the music. Do a harmonic analysis of the last few chords before each stop, and identify what type of cadence it is. Then see if you can begin to recognize the type of cadence just by listening to the music.

Exercise 5.6.1

Identify the type of cadence in each excerpt. (Hint: First identify the key and then do a harmonic analysis of the progression.

Figure 5.38

Read More..